Linguistic fieldwork in the Indonesian archipelago, throughout the 19th century, was largely the province of the Dutch Bible Society (NBG). Two Bible translators stand out for their contributions to linguistic scholarship: J.F.C. Gericke on Javanese in the late 1820s-1850s, and Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk on Toba Batak, Malay, Lampung, Balinese, and various other languages in the second half of the century. Their methods were as similar as their personalities were different. Gericke was pious, deferential, a bit naïve, and well liked by the colonial and Javanese elites; Van der Tuuk was an inveterate polemicist and open atheist who went half native, and whose eccentricities and vituperative letters earned him something of a legendary status.

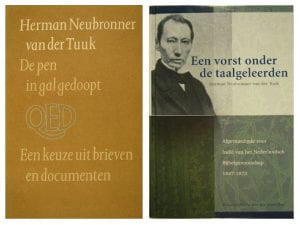

Both figure prominently in J.L. Swellengrebel’s history of the NBG in Indonesia, In Leijdeckers Voetspoor (2 vols., 1974-78); but while little has been written about Gericke since, Van der Tuuk’s correspondence as preserved in the NBG archives has been edited not once but twice. The titles of both collections are telling: Rob Nieuwenhuis’ pocket volume of letters selected for their historical or literary merit is called De Pen in Gal Gedoopt (the pen dipped in bile, 1962/82), while Kees Groeneboer’s near-exhaustive annotated edition bears the title Een Vorst onder de Taalgeleerden (a king among linguists, 2002). Annoyingly enough, the sole passages that Groeneboer sometimes intentionally omits are about linguistic details.

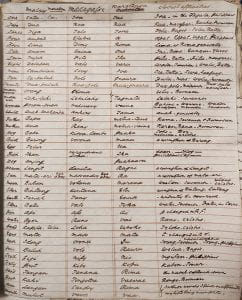

What both Gericke and Van der Tuuk (as well as other NBG translators) did was set up a philological cottage industry with up to half a dozen local staff. Together with their writers and language teachers (guru bahasa), they collected and edited Indonesian manuscripts, compiled a grammar and a dictionary of the target language before setting to translation work. In Gericke’s case, the preparatory work also included setting up a short-lived Javanese language institute at Surakarta (1832-42) modelled on Fort William College; Van der Tuuk devoted part of his energies to the revision of the main Dutch-Malay dictionary. On their deaths they left two of the richest collections of Indonesian manuscripts, now in Leiden University Library. But is particularly through their periodical, lengthy letters to the NBG that their work can be followed. In effect, these are among the most detailed (and in Gericke’s case, the first) linguistic fieldwork reports from the 19th century.

A Patchwork of Languages (and Religions)

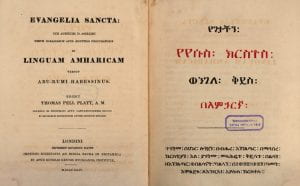

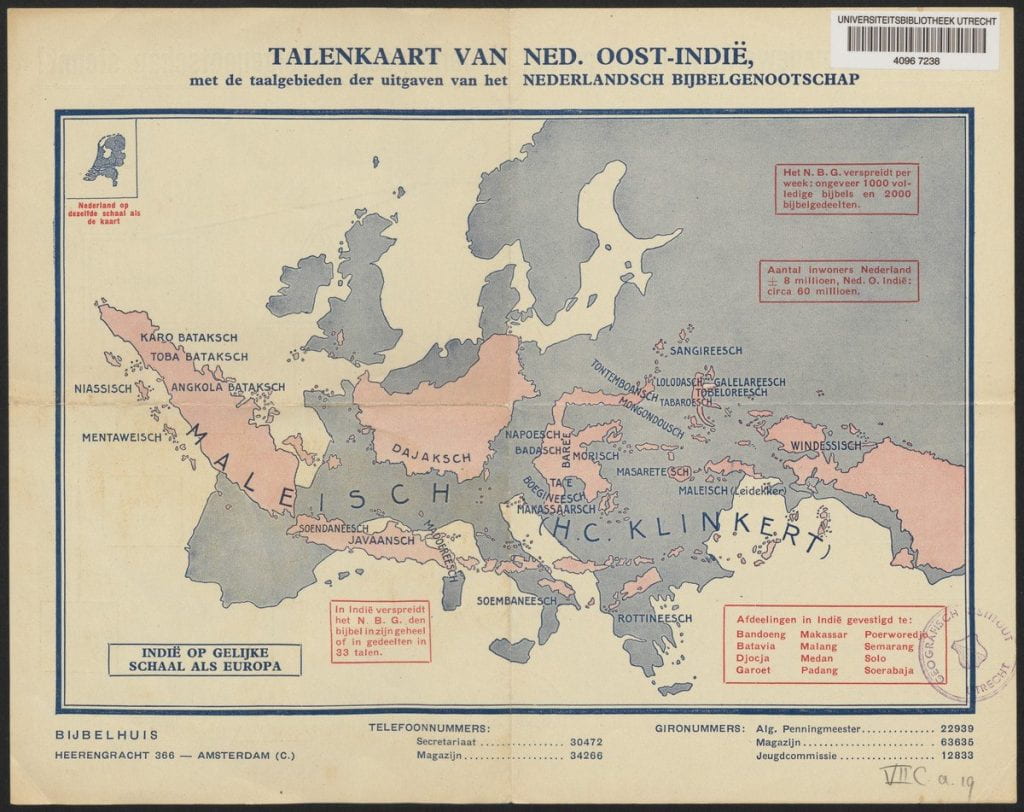

The colonial language dynamics within which the NBG operated was quite complicated. Colonial Indonesia (or the ‘Dutch East Indies’) was a patchwork of hundreds of languages, of which a dozen had their own writing systems. Malay was the lingua franca of the archipelago, of which the high literary register, written in adapted Arabic Javi script, differed quite strongly from the trade language and local varieties. Javanese was the largest language in terms of native speakers, with a literary tradition going back to the 9th or 10th century CE; at the core of that tradition was a corpus in Old Javanese (Kawi, ‘poet’, from Sanskrit kāvya) largely derived from Hindu epics and enacted at wayang shadow puppet plays. The Kawi corpus and language, however, had been preserved better on Bali, which had remained (and still is) largely Hindu while most of Java had converted to Islam. Batak, on which Van der Tuuk worked, was a language cluster on Central Sumatra of which most speakers adhered to Indigenous religious traditions. These were only some of the larger languages within the sphere of Dutch colonial and missionary activities; by 1936, the NBG proclaimed to have translated the Bible into 33 languages.

That linguistic patchwork also clearly reflected religious rivalries and religious syncretism. All the Indonesian writing systems, like those of Southern India, derived from Brahmi, and had developed together with the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism. Malay, on the other hand, was strongly linked to the spread of Islam, still ongoing in the 19th century, and the preponderance of Malay is the main reason why Dutch, though officially the language of colonial administration, did not become a ‘world language’ like French or Spanish. But Indonesian and especially Javanese Islam was thoroughly syncretic, with Sufi, Hindu, and Buddhist elements. When Gericke arrived in Surakarta to translate the Bible into Javanese, the Java War (1825-30) was still raging, in which Dutch colonial rule was challenged by the charismatic prince Diponegoro, who styled himself as both a traditional wayang hero and a sufi seer. In an early letter, Gericke recounts a visit to a “Javanese Seminary [pesantrèn ≈ madrassa] for the formation of priests” from which a lot of Diponegoro’s following had been recruited (as well as, presumably, Gericke’s own language teachers):

The number of students before the war was nearly 3000; now there are barely 200. The Emperor of Surakarta has bequeathed 31 dessas (villages) to it for its maintenance. Teaching consists mainly of learning to read the Qu’ran and memorizing the five daily prayers. Moreover students are educated in the secrets of the Buddhists and Betoros [Hindu deities], which have been preserved by the priests either through tradition or in their books after the conversion of the Javanese to Islam.

The letter is telling in a number of ways, not only about religious syncretism and religious politics but also about Gericke’s own attitudes. Though loyal to the Dutch authorities – he argued that “nothing can be achieved without them” – he became increasingly critical of their offhand treatment of the Javanese, and gained a lot of prestige by getting the head of the pesantrèn out of prison. After that, he visited the ruins of the Buddhist temple complex Borobudur, speculated about Buddhism as a purely philosophical religion, and dreamed of a journey to Bali to learn proper Kawi. He stands in stark contrast to his predecessor/rival as a translator, the Baptist missionary Gottlob Brückner, whose entire edition of the New Testament in Javanese, printed at Serampore, was seized by the Dutch authorities because he was also distributing anti-Islamic tracts right after the end of the Java War.

Van der Tuuk’s attitudes were a lot more antagonistic than Gericke’s. He regarded Bible translation as a hopeless task because each language was so deeply ingrained with a specific – religious – worldview that any translation would go either against the spirit of the language or of Christianity. Yet while he loathed the task, the one positive role he saw for Christianity was as an antidote to Islam, which he loathed even more and which was rapidly making inroads in the Batak lands. (Nowadays, Batak religiosity is roughly 55% Christian / 45% Islam.) Nor did he have many kind words to spare for Chinese traders, Javanese servants, Lampung peasants, the local nobility, Dutch missionaries, or the Gouvernement. Ironically, after an early incident in which he tendered his leave in a heavy fit of tropical fever, his relations with the NBG remained quite good throughout, although they knew full well that he was not a ‘theologizer’: they tolerated his eccentricities and heterodoxies because of his unmistakable merits as a linguist. When he finally left the NBG for a much-better paid position in the civil service in 1873, his last letter to them a month later already expressed regrets because his new employers were much more narrow-minded and less respectful of his intellectual independence.

Van der Tuuk’s cottage industry was also decidedly more messy. While Gericke mainly interacted with Javanese clergy and nobility and worked in the proximity of the court of Surakarta, Van der Tuuk decided quickly that Batak as spoken in the district capital was too ‘contaminated’ with Malay and settled in another harbour town, welcoming and paying anyone who could provide him with stories, manuscripts, or instruction in the various Batak dialects. One visitor recounts the scene:

He started by taking a teacher – a Guru – into his house. This man soon became his loyal companion, who ate and drank with him and accompanied him on many walks. Van der Tuuk asserted that, by talking to this Guru in all circumstances, he would soonest find out all the subtleties of the language. And it turned out he was right, for soon he felt able to have long discussions with all kinds of people from the hinterlands. He used the evenings to begin with his grammar; most often he was working until late at night. When I knocked on his door at six to go to the bustling river, he was often very sleepy still. I sometimes wondered at the sight of a half a dozen Batak strangers sound asleep in his parlour.

Van der Tuuk even floated the idea of marrying a Batak girl to learn the language more intimately – itself an indication of how, even while going half native, he still thought from a colonial perspective. He complained about the difficulty of finding good writers and servants in Barus, and two of his Batak teachers left after one of his fits of ire. If Gericke’s relationship with his teachers was much more formal, we also know more about his longtime instructor, Mas Ngabehi Ranuwito, than about any of Van der Tuuk’s associates, whom he hardly ever mentions by name.

The Resurrection of Kawi

Although there had been 17th/18th-century colonial studies of Malay (including various dictionaries and a Bible translation), systematic study of the languages of Indonesia only started with the creation of a central government during the British occupation of Java (1811-16). Kawi, as the most ancient and high-prestige language, played a central role in it: a hundred pages in Vice Governor Stamford Raffles’ History of Java (1817) are devoted to Javanese literature and a translation/synopsis/ commentary of the Brata Yudha (the 12th-century Kawi adaptation of a section of the Mahabharata), based on manuscripts plundered from the kraton (palace) of Yogyakarta and made with the aid of two Javanese nobles. Wilhelm von Humboldt’s posthumous magnum opus on Malayo-Polynesian languages, Über die Kawi-Sprache auf der Insel Java (1836-39), used this material as the footstone for a historical-comparative grammar, often approvingly citing Gericke’s Javanese primer and grammar. The same is true for the equally massive, unpublished Kawi-Javanese dictionary by his secretary, Eduard Buschmann.

This philologization – also of living languages like Malay and Javanese, in which Raffles and his deputy John Crawfurd collected hundreds of manuscripts – formed the background for Gericke’s and Van der Tuuk’s work on Javanese and Balinese, and especially their dictionaries. What they sought to do was not only to study the lexicon but also to actively purify the language by singling out the Kawi elements. Gericke, who regarded Surakarta Javanese as the uniform standard and other varieties not merely as dialects but as a deformed ‘patois’, sought to cultivate the Kawi element and increase the understanding of it; at the Javanese Institute he hosted fully staged wayang performances. Van der Tuuk, conversely, sought to promote the study and use of Balinese for its own sake, without the pedantic use of half-understood Kawi expressions:

Some Balinese, especially the learned, despise Balinese literature, saying of this or that Balinese writ anjar (it’s new), which means as much as not worth reading. This is also why one searches in vain for useful Balinese texts, because all that is written is full of Kawi words, some of which rendered opaque by excess display of learning. The commentaries to Kawi poems cannot be understood by anyone who does not practice Kawi, for the desire to look learned makes the interpreter use words which are even harder to understand than those they are meant to explain. Here Byron’s quip applies: I wish he had explained his explanation.

A complicating factor for Gericke, especially in Bible translation, was that the main division in Javanese (and in Balinese) is not between ‘elite’ and ‘common’ sociolects but between a ‘top-down’ register used towards people junior in age or rank (ngoko), and a more ornate and periphrastic ‘bottom-up’ register used to address superiors and elders (kromo). This prevades every aspect of the language, with parallel words for nearly everything. Gericke set out to translate the Bible in kromo which was more humble and dignified but changed his mind at a late stage in the translation process because ngoko was more clear and succinct and because the humble register did not convey enough authority. In passages with shifts in speaker perspective, he was dragged into a game of language pingpong:

A small start that I have made with the translations of the Psalms convinces me of the difficulties. […] For example, the second Psalm has seven changes of speaker, which the language must adapt to.

Verse 1 and 2, the Poet speaks Kromo; Verse 3, the enemies of the King upon Zion, as rebels, speak Ngoko; Verse 4 and 5, the Poet again speaks Kromo; Verse 6, God himself speaks Ngoko, differing from that of the rebels; first half of Verse 7, the Anointed speaks Kromo; the other half of the seventh to the end of the ninth verse, containing the words of the Lord to his Anointed One, are Ngoko again; in the final three verses, the Poet speaks Kromo in his admonition to the rebels.

If one sought to use one and the same language in the entire Psalm, no Javanese would understand it. The difference between Kromo and Ngoko is often as big as between Dutch and Polish.

Note that Psalms 2:8 is where God says, in one of the most colonial passages in the Bible, “Ask of Me, and I will give You / The nations for Your inheritance / And the ends of the Earth for Your possession”.

Legacies

Gericke was repatriated in 1857 in what his physician described as “a general state of debility”, and though he seemed to have recovered somewhat back in Europe, he died during a family visit in Düsseldorf towards the end of that year. His Javanese Bible translation, for all its philological merits, did not become the standard translation: it lost out eventually against a more accessible rival version made by the disgruntled missionary Pieter Jansz and published by the BFBS. Van der Tuuk’s Toba Batak Bible also did not establish a lasting standard, because the language changed too much through colonisation and evangelisation. This was as he had predicted, arguing that the Biblical register had to develop in religious practice; accordingly, his work was later revised and used as a matrix by Rhenish missionaries whom he had trained. Van der Tuuk spent his last two decades on Bali, increasingly isolated from Dutch colonial society, working on his four-volume Kawi-Balinese-Dutch dictionary that appeared posthumously. On his death the notary listed among his possessions nearly fl. 140.000 in bonds and assets, the richest manuscript collection in Indonesia, some pots and pans, two donkeys, a dozen chickens, and a hut valued at ten guilders.