Two unpublished histories of the British and Foreign Bible Society were written in the 1820s to 1830s (BFBS Archives, Cambridge University Library, GBR/0374/BFBS/BSA/E3/8/1 and E3/8/2). It is unclear to me why there were two, both by BFBS staff, written at roughly the same time; they cover much the same topics, figures, and languages and do not express notably strong or divergent views. What is clearer is why they were never published. Both manuscripts are very lengthy compilations of excerpts, transcripts, summaries, and in the case of the largest manuscript, of literal cutting and pasting from printed BFBS reports. All that material is arranged by language, with a chapter for each language into which the Bible was translated before or during that period, and no attempt at overarching narrative or analysis.

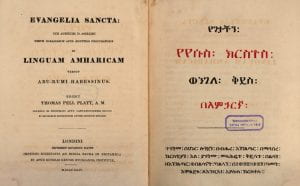

The biggest of the two manuscripts – in 15 volumes and envelopes of some 200 quarto pages each – was compiled by Thomas Pell Platt, the BFBS librarian between 1822-1831 and editor of its Greek, Amharic, and Ethiopic (Geez) versions. By far the largest chapter, filling two half-volumes, is taken up by the Serampore Mission. Serampore was a Danish colony near Calcutta, where a trio of Baptist missionaries churned out the unlikely number of 34 translations between 1800-1837 (i.e. in part before the BFBS was founded). What makes the chapter so large is also that it is largely a collage of the successive printed reports of the Serampore Brethren – reports that are otherwise hard to find even in Cambridge University Library. The same goes for Platt’s chapter about Sinhalese (the main language of Sri Lanka), where disagreements between missionaries turned into a veritable translation war. This recycling process makes Platt’s history a valuable historical source even despite its lack of originality.

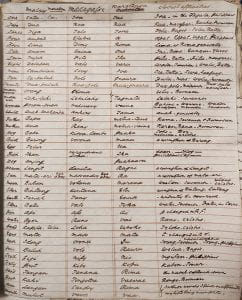

The other manuscript, though also filling 15 octavo notebooks, is considerably more condensed, enough so to fit into a single archive box. Its author is listed as John Radley, about whom less is known. Still the linguistic information is generally much richer than in Platt’s larger volumes: Radley provides comparative vocabularies and samples of alphabets as well as sketch language maps of Sulawesi and the upper Ganges region. More than Platt, he is inclined to cite and draw his information from recent non-missionary sources; his focus is on the missionary frontier in South/East Asia, whereas half of Platt’s history is devoted to larger and smaller European languages. Accordingly, Radley mixes missionary history with late enlightenment ethnography, taken from the works of British scholar-administrators in India and Indonesia (Colebrooke, Marsden, Raffles, Crawfurd).

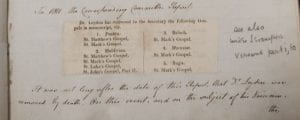

What both manuscripts show us is how Bible translation resulted in a linguistic world map. Though written by philologically versed authors, neither was intended as a language encycylopaedia; but they contribute as least as much to our understanding of linguistic dynamics as of missionary history, and with its collection of linguistic ‘specimens’, Radley’s history leans towards a missionary Mithridates. The sheer multilingual scope and – sometimes misguided – optimism of the more industrious translators is staggering. In March 1810, the linguistic prodigy John Leyden promised to deliver gospels in “Siamese, Macassar, Bugis, Afghan or Pushtoo, Rakheng, Moldivian & Jaghatai” (accordingly grouped into one chapter in Platt’s history, although they belong to different regions and language families). With the aid of an unspecified number of “persons who assist Leyden in his literary researches” he estimated that “a year and a half might be sufficient for completing the Afghan, Jaghatai, and Siamese versions, and most probably the Bugis and Macasar” – and true enough, before his untimely death on Java 17 months later, he had pulled off complete gospels in Maldivian, Mark and Matthew in Pashtu, and Mark in Balochi, Makassarese, and Bugis, the latter two delayed by illness of his interpreter.

Sometimes that optimism was sheer naïveté. Joshua Marshman, one of the Serampore trio of translators, cheerfully announced that he was first translating Confucius with the aid of the Chinese Armenian Joannes Lassar (Hovhannes Ghazarian) and an unnamed ‘Chinese assistant’, and then using the knowledge of Chinese thus acquired in translating the Bible. For all his insistence on method and autopsy, he never set foot in China; it is unsurprising that Chinese converts were rather won by other versions, like that of Karl Gützlaff and Robert Morrison (a work that inadvertently inspired the Taiping Rebellion, a mid-century syncretic millenarian movement that left 10-20 million Chinese dead). William Carey’s Marathi version fell flat for the plain reason that his munshi spoke ‘corrupt’ or nonstandard Marathi. But even Carey’s Sanskrit Bible, though more of a status object than a practical tool for proselytization, had its uses as a matrix for other translations.

Triangulation and Translation War

The story of Sinhalese, narrated in detail by both Platt and Radley, is illustrative in this regard, and in other ways. A first translation had been made in the early 18th century by the Dutch clergyman Willem Konijn, which was judged too plain as well as “unintelligible, formed according to the Dutch idiom, and not according to the Cingalese” by the Wesleyan missionaries after the British annexation of the colony. A colonial administrator with a passion for languages, William Tolfrey, undertook a new version with the aid of the converted Buddhist priest Abraham de Thomas and other (ex-)Buddhist clerics. To ensure that the new version was less foreign and more up to Sinhalese literary standards, a parallel version was made in Pali, the holy language of Theravada Buddhism:

To judge of the extent & appreciate the merit of Mr Tolfrey’s labours, it ought to be stated, that he carried forward the Cingalese translation in connexion with a second translation of Dr Carey’s version of the Sanscrit version into Pali; judging it expedient to render every verse into the Pali before it could be revised with effect in the Cingalese. The old Cingalese text was then revisited – it was afterwards compared with the Pali, & also with the excellent Tamul translation of Fabricius; in which the form of expression is so much alike, as to run easily from the Pali into the Cingalese: – but all with continual reference to the original Greek, & our own English version. The Pali though hereafter a work of great utility, only served at present to give precision & clearness to the Cingalese version.

That is from Radley’s History, notebook VI. More detail on the translation process is provided in Platt’s chapter on Pali:

The Pali translation is conducted in this manner. Mr Tolfrey reads from the text of Dr Carey’s Sanskrit Testament a certain number of verses to Don Abraham de Thomas, who writes the whole passage in Pali, as nearly as the idiom of that kindred language will admit. They afterward read over the Pali together, compare it verse by verse with the Sanskrit, and make any correction which in their judgement may be necessary. The Bengalee version is also often consulted in difficult passages, when the Sanskrit phrases are not easily expressed in Pali.

Moreover, their Pali version was used as a matrix by “two learned priests of Matura, Karratote Unnanse, and Bowila Unnanse […] who are both ignorant of English, and totally unacquainted with the Scriptures” for translating several chapters into common Sinhalese, so that it would be “perfectly intelligible to the natives, and free from all improper phrases or expressions borrowed from the English or Dutch languages”. Tolfrey sadly died in early 1817, with half the work done; fortunately for the BFBS, a committee of four missionaries who had been taught by Tolfrey stepped in to set forth his translation, following his ‘style &c.’ as closely as possible, and completed it by 1823.

That was not the end of the story. If Konijn’s version had been too plain, the new version was now criticized for being too difficult for ordinary Sinhalese, who needed a glossary. A remark in the BFBS reports that “The Natives of Ceylon were under the dominion of Europeans for two hundred and fifty years before their conquerors gave them any part of the word of God” provoked an angry letter from the Dutch Bible Society. CMS missionary Samuel Lambrick and three of his brethren protested against the new version because the Word should be for the poor, and because the new version used concepts and honorifics that were Buddhist in origin, thus importing heathenism into the holy writ. The local Bible Society invited Lambrick to provide his own version of six chapters of Matthew, which were not met with approval, after which he ended up publishing a simplified Sinhalese Book of Common Prayer and a Sinhalese Grammar at the Church Mission Press.

Time, Souls, and Money

There is no direct correlation between the time and effort involved in these translations and their impact. Although the Ceylon mission proudly claimed to have 10,000 native children in mission schools by the 1820s, with enough demand for 50,000 if there had been enough missionary teachers, Buddhism is still by far the majority religion on Sri Lanka, and most Sri Lankan Christians nowadays are Catholics. The first Javanese translation (1829), by the Baptist missionary Gottlob Brückner, though completed in the early 1820s, was held up by technical difficulties and the Java War (1825-30), and finally printed at Serampore, only to blocked by Dutch colonial authorities who wanted to avoid causing new unrests. The Dutch Bible Society’s own version was two more decades in the making, only to be eclipsed later by a less philological BFBS rival version. On the whole, missionary efforts were much more effective where they sought to replace Indigenous religions, like in Oceania, than when they were up against other ‘world religions’ with literary canons like Hinduism, Buddhism, and especially Islam. Inspired by the success of the LMS mission on Tahiti, and given the great similarities between Polynesian languages, the BFBS sought to save time and effort by using Tahitian as a lingua franca for other parts of Polynesia, but this turned out to be harder than expected.

A case in which Platt was personally involved as an editor, although he does not mention his own role, was Amharic. In 1820 there were painstaking negotiations (mediated through the French Orientalist mogul Sylvestre de Sacy and the British consul in Cairo) with the ex-priest and dragoman Jean-Louis Asselin de Cherville who wanted to sell a manuscript of a complete Amharic Bible translation for £ 1500. The BFBS offered only £ 750, which was already more than its standard fee of £ 500, in spite of doubts about a translation made by one man and not directly from Greek and Hebrew. In fact it had not been made by Asselin but by the Ethiopian priest Abu Rumi who lived with him in Cairo; in Ethiopia, Amharic was traditionally the language of the court whereas Geez was the language of the Bible. Eventually, Asselin and the BFBS agreed upon £ 1250, and the 9539-page manuscript was inspected by its indefatigable philological factotum, Professor Samuel Lee. (Apart from the details about the negotiations, the story can be read at greater length in William Jowett’s Christian Researches in the Mediterranean (1822), 197-204.) But preparing the manuscript for print took the BFBS nearly a quarter of a century: Gospels in 1824, the New Testament in 1828, and the whole Bible in 1844. Platt does not tell anything about the twenty-four-year editing process, but one can easily imagine him wearily looking up to the skies.